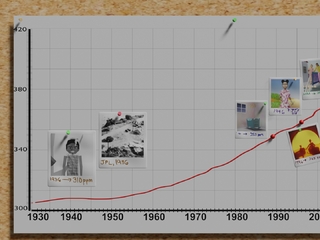

A NASA satellite managed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory is measuring the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But things get tricky when that CO2 finds a place to hide.

Carbon dioxide is great at finding hiding places.

One favorite hiding place? Trees. In fact, the world’s forests soak up about a quarter of all human emissions of CO2.

But there’s another hiding spot that’s less obvious: the ocean.

Every year, the ocean is estimated to absorb about as much CO2 as all the world’s forests do. It may seem like a lucky break for humanity – the more the ocean can absorb, the less CO2 remains in the atmosphere to drive the greenhouse effect that’s behind climate change.

But nothing in nature is ever free. Just ask the indigenous tribes that dot the Pacific Coast in Washington State. For people like Janine Ledford of the Makah Tribe, the ocean is just a walk or bike ride away, and the whispers of rushing waves reverberate wherever she goes. Multiple times a year, Janine and her son walk the short distance to gather shellfish along the shores of their reservation. If they’re hungry for clams, they go to the sandy beaches. If they’re after gooseneck barnacles or mussels, they head for the salt-splashed rocks.

“These are traditional foods that we’ve harvested for generations and generations,” Janine says, noting that gathering seafood on the Makah reservation is restricted to Makah tribal members. She steams the barnacles, and boils the crabs, and often goes next-door to share the meal with her aunt. “Some people dip them in butter, but they taste really good plain.”

Up and down the Washington State coast, other members of indigenous groups rely on shellfish for food or for livelihoods just the same as Janine. That’s why biologists and scientists are concerned about all the CO2 the ocean absorbs. Absorbing CO2 makes the ocean more acidic (known as “ocean acidification”), and makes it difficult for crabs, clams, and other shellfish to grow their shells as strong as they need to be. For these animals, their shells are their homes that they use for protection, and they can die as a result of ocean acidity.

“It’s a multi-stressor problem,” says Joe Schumacker, a marine scientist with the Quinault Indian Nation further down the coast. “We have multiple issues: warmer waters, less oxygen in the water, and now combining that with ocean acidification is a triple whammy. If we get a perfect storm of bad events, that can wipe out an entire shellfish population. That’s when we’ll really feel this.”

There have already been some isolated shellfish wipe-outs on the northwest Pacific Coast linked to ocean acidity, and since CO2 emissions are continuing to increase globally, there may be worse yet to come.

CO2 may try to hide, but a NASA satellite can seek it out

When those wipe-outs happened, biologists didn’t even know why at first. It took some good investigative science to make the connection with ocean acidity, says Joe.

It didn’t help that measuring ocean acidity isn’t the easiest thing. “We have sensors to test for carbon dioxide in the ocean, but the sensors get tossed around a lot in the waves,” says Scott Mazzone, who works as a shellfish biologist for the Quinault Indian Nation. Plus, the ocean is so enormous, and coastlines are endless – there are not enough moorings and buoys to sample it all.

This is exactly the type of situation where a NASA satellite can come in handy – and in this case, it’s the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2. This satellite takes millions of measurements of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere from space.

Now, the difference is, OCO-2 doesn’t measure what’s in the ocean; it only measures the carbon dioxide in the air above it. But sometimes, that’s enough. As Abhishek Chatterjee, deputy project scientist for OCO-2, says, “Where there are large changes happening in the ocean uptake of CO2, we can observe that using the satellite.”

In fact, a few years ago, Abhishek and some of his colleagues used OCO-2 to uncover a sharp decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide over a far-flung stretch the tropical Pacific Ocean. It was an El Niño year, and it caused a big response in the ocean – a response that might have gone unnoticed, given it happened in a remote area where few moorings and buoys are present. But OCO-2, peering down from the cusp of Earth’s atmosphere, gathered data that made the effects easier to study.

OCO-2 helps scientists finds carbon sinks like this, whether in the ocean or the forests, all over the world. The consequent changes these sinks cause in ocean chemistry and ecology can have a steep impact on people like Janine.

From toddlerhood to old age, shellfish traditions are a key part of Makah life. In the Makah preschool, four-year-olds troop down to the beach under the watchful eyes of their instructors, for their earliest memories of clam-digging. Agile adults will clamber over rocks even in slippery, icy conditions to pluck barnacles and mussels off rocks. They share what they gather with the elderly, and bowls brimming with delicious shellfish are often a prime feature at big community dinners and potlatches.

Abhishek hopes more scientists will start using OCO-2 to study ocean acidification along coastlines like the Makah’s. It’s harder to measure the ocean uptake of CO2 there compared to the middle of the Pacific Ocean, he points out. Depending on how the wind is blowing, more often than not the satellite data will be a confusing mix of signals from the water and the land, making it extremely challenging to tease out clear information.

It doesn’t mean it’s impossible, though.

There are millions of ocean soundings, Abhishek points out, from both OCO-2 and OCO-3, its sister instrument on the International Space Station. All that data holds exciting potential for more research on how ocean acidity will affect ecosystems. And ultimately, it can help inform people like Janine and other coastal-dwelling seafood lovers about what they might expect in the future.

Ocean acidification is a big enough issue that even high-school students learn about it: