I had been watching people at JPL doing what I felt was interesting work. It seemed hard, but I thought, “I’m not a stupid girl; I can go to college and learn how to do this stuff,” so that’s what I did.

Cozette Parker grew up bike-riding, roller skating, and scraping her knees from falls in Pasadena, right in the shadow of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. But she didn’t know what JPL did or have any idea she’d end up working there. What was her path to JPL? Read about it in her own words.

What did you enjoy doing as a kid?

I grew up in the ‘70s in the Pasadena area and liked roller skating, bike-riding, and hanging out with my friends. I got a lot of skinned knees while skating and biking down hills because I couldn’t figure out how to stop.

I was also an avid reader. My best friend introduced me to Nancy Drew and Little House on the Prairie books. Charlotte’s Web, James and the Giant Peach, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory – I loved all of that.

Since you grew up right next to JPL, was it always your dream to work there?

I always knew about JPL, but I wasn’t sure what they did. I just knew they were a huge employer. My previous jobs were actually not even close to what JPL does. First, I worked at a fast food ice cream place. I was 14, but I told them I was 16 because that was the minimum age. I wasn’t a great employee. I gave away a lot of food, LOL. As a high school junior, I started at a coffee shop called Salt Shaker, where I was a hostess and waitress for a couple of years. When I graduated from high school, I was employed in a variety of different jobs including customer service at a local Fotomat, telephone operator, and school bus driver. I was robbed twice in one week at the Fotomat, so my mom said, “That’s it, you’re quitting!”

How did you get your foot in the door at JPL?

I was doing office work for an insurance brokerage. I had done typing and shorthand in high school, so I was trained for it. I worked in a 14th-floor office in the Century City business district of Los Angeles. When I left that job, I had a girlfriend in Pasadena who had just started working at JPL. I called her and asked, “What do I need to do to get into JPL?” She recommended I go through a temp agency. My temp job at JPL lasted three weeks, and then I was offered a permanent position supporting the Voyager mission. I was a good typist and staff assistant, so it wasn’t that hard for me to get on with my new job. It was also way more laid-back at JPL. Skirts and pumps were no longer necessary, but I ruined several pairs of shoes when my heels got caught in the tiles on the JPL mall!

You switched from staff assistant work to engineering work. How did you make it happen?

I had been at JPL for five years. I had a friend who was starting college and she told me, “You know, you should probably go to college.” I said, “I work all the time; I don’t have time for that.” But after she’d done it for a semester or a year, I said, “Okay, I’m coming.” I started at East Los Angeles College, a community college, and got an Associate Degree in Liberal Studies. When I finished, I decided I wanted to move onto something technical. I had been watching people at JPL doing what I felt was interesting work. It seemed hard, but I thought, “I’m not a stupid girl; I can go to college and learn how to do this stuff,” so that’s what I did. That’s when I transferred to the University of La Verne, a private school in Los Angeles County.

I got all A’s, except for a B in speech. I even did well in physics. I had never taken physics in high school, so I was completely intimidated because it sounded so hard, and I ended up loving it. I told everyone I knew at JPL that I’m in college and I’m going to want a job. And anytime someone had a little engineering job they wanted to be done, I told them, “I’m your girl. I can get it done.” I remember coming to JPL during a weekend, crawling under a desk, breaking my nails, pulling cables, and connecting things. So when I finished my bachelor’s degree, one of the supervisors I had supported for years offered me my first engineering job at JPL.

Tell us about your job commanding spacecraft.

I was a mission controller for Ulysses, a probe that orbited the Sun. I never imagined I would be sending commands to a spacecraft millions and millions of miles away. I got to see one of the antennas we used at the Goldstone Complex. It’s out in the desert in California, with turtles and donkeys all over, and it was so awesome. I flew there on a NASA plane that has since been decommissioned. That was an experience I do not care to repeat (the plane ride, that is). Stand next to these antennas—they’re humongous. It’s amazing what we do at JPL, to be in contact with spacecraft flying millions of miles away. The Ulysses mission ended in 2009, and during its final moments, all of us mission controllers went to the operations area and watched as the communications ceased. Ulysses just floated off into space.

You now work on NASA’s OCO-3 mission. What do you do?

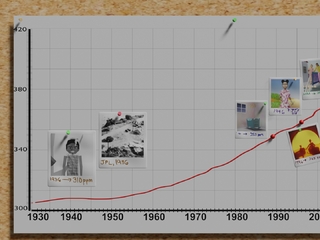

I’m still very much in training and learning a lot of new things. I’m thankful to be on a team – we back each other up. OCO-3 (Orbiting Carbon Observatory 3) is located on the International Space Station (ISS). It’s a very sensitive instrument called a spectrometer. It has to avoid direct sunlight because it can damage OCO-3’s detectors. So we sometimes have to use the pointing mirror assembly to stow the instrument, depending on what the ISS is doing. We have to be very reactive if a visiting vehicle comes in bringing supplies to the astronauts, or a new instrument is getting installed. And for example, sometimes the ISS flies backward. So we tuck the instrument away until it’s safe for it to point to Earth again and continue gathering data. We create a week’s worth of commands that we send on Thursday, and then we make changes based on if the ISS has a change in schedule.

Since OCO-3 is involved in monitoring carbon dioxide (CO2) levels on Earth, has this affected your own CO2 emissions?

I try to. I turn off all the lights in the house unless I’m using them. And I recycle plastics. I’m a car person, though; I just love cars. If I could afford a brand-new electric car with a lot of power, I would do it. Call me Danica Patrick in another life. I would love to be a race car driver.

What are the most important things to you?

I come from a big family with lots of nieces and nephews. I have a niece four years younger than me, so she’s like a sister-niece, and her two boys are very dear to my heart. They’re adults now. I have another nephew who has two little girls; they are the most precious things in the world.

Imagine your younger self – what advice or words of hope and encouragement would you give her if she were starting out today?

Go to college right after high school. Do not fool around; you know what I mean? When I got out of high school, I thought college wasn’t for me. But I was a gifted student. I could have applied for scholarships and received them, but I just wasn’t interested at that time. Community colleges are very good if you don’t know what you want to study. Get your prerequisites out of the way for way less money. That worked really well for me. When I finished community college, I had a direction for what to do next. Employers want to know that you can learn. Having a degree means that you’re teachable.