When Matthäus Kiel first moved to Los Angeles in 2016, he knew what he was getting into.

“It’s a smoggy city with tons of pollution,” Matthäus says. Even though it’s gotten better, Los Angeles still ranks as the city with the worst air pollution in the US. And air pollution often goes hand-in-hand with high levels of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions behind climate change. To Matthäus, though, this was not just a challenge, but an exciting opportunity.

He came to Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to work on satellites that measure concentrations of CO2 from space. “Since the greenhouse gases and CO2 are so high here, it’s the perfect place to study what the satellites are measuring.”

These satellite instruments, NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) series, are built and managed at JPL. They launched in 2014 and 2019, respectively, and are still fairly new. Matthäus wants to let as many people as possible see what they are capable of.

“We go to conferences and meetings to present the new data to other scientists as well as the public, and the best way to show it is through a little movie.”

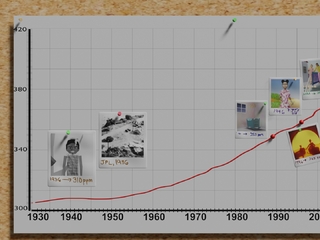

Matthäus made an animation of the special data from the OCO-3 instrument perched on the International Space Station:

No other current CO2-measuring satellite can capture a whole city at a time with such high detail. OCO-3 has a special camera that can pivot and take row after row of data side-by-side, all in about two minutes – just how the data unfolds in Matthäus’ animation. It makes it possible to see the shroud of CO2 over Los Angeles all at once (plus for the 100 top CO2-emitting cities in the world, and even for some of the largest power plants).

Everyone in Los Angeles contributes to this CO2 shroud, including Matthäus himself. Using a free online calculator, he calculated the amount of fossil fuels that’s being burned to support his lifestyle. Then he went about trying to reduce it.

For example, he’s been replacing all his light bulbs with more efficient LEDs, and replacing appliances with energy-efficient ones. “They make it easy nowadays; there are often labels in place to see the efficiency.” Matthäus also sees many others in Los Angeles trying to reduce their carbon footprint. “For example, I’ve never seen as many electric cars in the street as I have here.”

Peter Kalmus, a JPL data scientist, has been on a mission since 2010 to reduce his carbon footprint as much as possible. “I felt frustration and desperation about climate inaction building up, and it struck me one day that I’m burning a lot of fossil fuel.” Like Matthäus, Peter was able to create a ledger of how much fossil fuel burning was supporting his lifestyle, and over a two-year period, he systematically brought it down until he was consuming 1/10th the amount of a typical American.

“I found I liked living with less fossil fuels,” Peter says. The biggest sacrifice for him was that he quit traveling via airplanes in 2012, since airplanes are one of the most carbon-intense modes of transportation. “Not flying has limited my career – it’s made it harder to get involved with international collaborations.”

He also wishes that Los Angeles were better organized in ways that would make it easier to reduce emissions. For example, the subway system in Los Angeles is not very dense, and Peter lives too far from the nearest stop to use it regularly. For a few years, he tried to stick to biking around the city, but sometimes he needs to “schlep my kids around to cello lessons and the like, and it’s hard to bike with a cello.” For that reason, he purchased a used electric car for about $7,000 in 2019. He charges his electric car by using the solar roof he has installed at his home. While this is preferable to driving a gas-powered car, Peter wishes there were better options. “I see it as a shame that I’m contributing to car culture. It’s a part of my life that I don’t like. I wish we lived in a system where having kids didn’t necessitate having a car.”

Cost is another issue that makes it harder to reduce emissions. Gloria Medina is the executive director of SCOPE-Los Angeles and advocates for communities in South Los Angeles. They’ve gone door-to-door to provide information and drum up support for things like solar panels and electric cars. “Folks are excited and would love to do it,” says Gloria. “They understand it’s good for the environment.” But even with rebates, the costs can be out-of-reach and extra hurdles arise. “Some homes may be older. When you think about placing a solar panel on a roof that’s not kept up, it just doesn’t work. It requires upgrades to the roof first.” And as for electric cars, South Los Angeles is missing some key infrastructure. “If you drive around, you won’t find electric charging stations. So even if you can afford the car, you still cannot power your vehicle in your neighborhood.”

Currently, electrical appliance bills are more expensive than gas bills, and that’s another area of concern. “It drives communities out if they cannot afford transitioning to either the new electric appliances or the higher electricity bill,” says Gloria. “We do want decarbonization. It’s a good thing. But the most vulnerable folks who are already at risk of being displaced should be part of the conversation of what this transition will look like.”

At any rate, South Los Angeles is not actually the bigger producer of CO2 emissions in the city. That distinction belongs to the wealthier areas. “People like to have 7,000-square-foot houses here, which have a huge appetite for energy,” says Peter. He says it’s not just about transitioning to more efficient appliances and solar panels—it’s about reducing demand for energy in the first place.

If Los Angeles truly started reducing its emissions, however, Matthäus has some surprising news: the brilliant colors in his animation over the city won’t be budging any time soon, even if new CO2 emissions drop to zero.

“The lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere is several hundred years. Therefore, once Los Angeles becomes carbon neutral, while the animation colors will no longer become brighter, they will stay at a similar brightness for decades.”