Tom Pongetti once saw a tree explode.

It was September 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic shuttered most on-site operations at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). At the same time, one of the most devastating fires ever to accost Los Angeles was wreaking havoc on the mountain slopes above JPL.

“It was terrifying,” Tom remembers. “The fire got really close, within 50 feet of our lab facility.” The JPL facility he’s talking about, CLARS (California Laboratory for Atmospheric Remote Sensing), is about 5,700 feet above Los Angeles, clinging to the cliffside of Mt. Wilson. It’s thickly framed by oaks, pines, and firs – but all were sizzling with flames that day.

In particular, Tom recalls a giant live oak tree that was flourishing and healthy before the fire — in other words, jam-packed with carbon. Healthy forests are called “carbon sinks” precisely because they store carbon that otherwise would escape to the atmosphere. At least until those forests burn.

Watching through the webcam that live-streamed the fire, day and night, to evacuated personnel, Tom could see life slowly leaking out of the tree.

“There was a bunch of fire on the steep cliff below the tree, burning up the ridge, and the tree was getting hit by all the smoke and hot air blowing off the fire.”

After half a day, the tree finally burst into flames. It was a mark of how fierce the fire was because oak trees are known for their fire resistance. “It’s actually pretty hard to catch oak leaves on fire,” Tom notes. “But it dried out so much, it just became a fuel source.”

When fires like this happen, NASA-JPL satellites have a bird’s-eye view. First, there’s the MISR satellite instrument that observes long spirals of gray smoke. There’s the ASTER satellite instrument, which delineates the scorched earth left after the fire.

And then, there’s the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2).

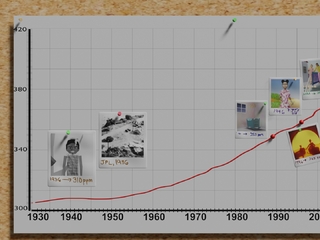

Like its name suggests, OCO-2 measures carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. Large forest fires pump out so much CO2 that the concentration becomes noticeably higher over those areas. The contribution ends up equal to just under 5% of global CO2 emissions. In places as far-flung as Indonesia, the Brazilian Amazon, and southern California, scientists have used OCO-2 to show the aftermath of large forest fires.

For example, an increasing number of fires have afflicted the Amazon rainforest in Brazil ever since 2012. Fires here are different than in California. While the western U.S. is so dry that a fire can quickly spiral out of control, the rainforest is too moist to allow massive conflagrations. Instead, the Amazon rainforest is pockmarked with smaller-scale fires deliberately stoked to make way for farms and pastures. Each individual fire may be small; but there’s so many of them it’s not lost on OCO-2. The satellite clearly shows the swelling in atmospheric CO2 over the Amazon during the months of peak fires.

Incidentally, even the CLARS facility, where Tom Pongetti was keeping an agonized watch through his webcam, can measure CO2 in the atmosphere. In fact, CLARS and OCO-2 even use the same wavelengths of light to make the measurements. Of course, CLARS is not an orbiting satellite in space; it sits stationary on its oak-ringed cliff, looking down into the valley where Los Angeles lies. Still, both OCO-2 and CLARS data help us understand how CO2 is increasing in the atmosphere.

And at that moment, Tom had no idea what might happen to the facility he helped install back when CLARS was built 10 years earlier.

“I was trying to get my work done, but I was just glued to the webcam,” Tom recalls. “We knew there was nothing we could do at that point, that it was in the hands of the firefighters. We were either going to watch the whole facility burn up in real time, or watch the firefighters save it.”

When the oak tree burst into flames, the firefighters on the webcam all dropped their hoses and ran up the cliffside away from the site. Tom thought, “okay, we’re going to lose the site, it’s going to be severely damaged at least.”

But then, a fire helicopter came to the rescue, filled brimful with water from a local reservoir. Tom watched with excitement as water doused the flames, after which the firefighters came back to finish the job.

“The firefighters were the heroes, the star of the show,” Tom praised. And these days, that oak tree that exploded into smoke is showing signs of life, putting out shy shoots of green. When Tom drove through burned mountain slopes a year later, he found a scene of ecosystem rebirth. “As far as the eye could see, everything was just covered in wildflowers. White, orange, purple … the Earth does have a way of growing back, it does have some beauty there after the ash and everything has passed.”

He knows, though, that the CLARS site is at the mercy of an ever-drier, ever-hotter climate that will likely fuel fiercer fires to come. Which in turn, will burn more trees, release more CO2 to the atmosphere, and add more fuel to global warming. It’s a vicious cycle. OCO-2 and similar satellites will witness it all, providing data to help scientists understand our changing planet.

Acknowledgments: Ane Alencar, Director of Science at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), contributed valuable information to this article.