Green spaces can create urban oases, and a NASA mission has the data to show they also help pull carbon dioxide out of the air in cities.

At first, it’s just a smudge on the horizon. That’s generally what you see when you start approaching a large American city, whether by road or train track. It’s only as you get closer that the skyline emerges: tall towers, glossy steel, construction cranes. Almost always, the view is wrapped in the thin, filmy gauze of smoke and soot. And where there is smoke and soot, there is often carbon dioxide.

Maryum Rasool experiences that gaseous haze every time she drives towards the colossal cityscape that is Chicago. “It’s unfortunate,” she says, “because otherwise, it’s such a beautiful skyline.” Chicago is a four-hour drive from Flint, Michigan, where Maryum lives and serves as the executive director of a youth center. Pollution aside, she enjoys her visits to Chicago. The sights kindle her imagination. Once, she was enchanted by an outdoor “green wall” at a museum – a vertical garden full of living plants. “It was unique and served a purpose,” Maryum recalls, and gave her inspiration to create something similar at the Flint youth center.

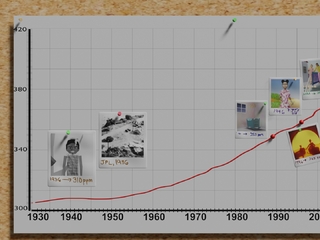

These small details of Maryum’s adventures in Chicago can actually be seen from space, via satellite. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has launched many satellites that study Earth. One of these, the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2), can measure the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and shows that in cities these measurements continue shooting upwards like a run-away rocket. But OCO-2 also shows there is something pushing, albeit not entirely successfully, at the brakes: the parks, trees, and green walls that dot the city streets.

Maryum had been hoping to install something like the green wall at her youth center in Flint for a while. The spark started with a few nine-and-ten-year-olds at the Sylvester Broome Empowerment Village. Every day, Flint kids stop by the Village to take lessons in watercolors, music production, and dance, but in this case, Maryum remembers, it was the kids who wanted to give the lessons.

“It was a couple of summers ago, and some younger littles were upset at the litter they saw in their neighborhoods,” she says. These students both pushed to secure plastic bottle recycling bins at the Empowerment Village, and wanted to educate their parents and other adults in the community about being better stewards of the planet. Maryum felt the green wall would be a bold, fresh approach to help start those conversations.

These green walls – both the one that Maryum saw in Chicago and the one she hopes will grace the youth center in Flint – inject plant-life into cities. They do their bit to counteract the haze of smoke, soot, and carbon dioxide over cities, something which is sorely needed. Ever since it launched in 2014, OCO-2 has revealed how cities have higher carbon dioxide levels compared to their rural surroundings. This is especially true for large cities in the Northern Hemisphere. Chicago, New York, Los Angeles – these cities stick out in OCO-2 data for their elevated carbon dioxide levels.

Cities have some built-in advantages to cut down on carbon emissions: for example, you might catch a bus to the library or walk to school rather than drive, and if you must travel by car, the distance might be shorter. In spite of all this, cities like Chicago remain carbon hotspots due to the sheer numbers of people living there. (There’s also evidence suggesting that affluent city populations consume more goods and resources compared to rural ones, likewise driving up the urban carbon footprint.)

But green spaces can make a difference. OCO-2 data shows that every spring, when the flowers unfurl and the shy leaves peep forth, carbon dioxide levels drop in cities. To be sure, they start rising again in the fall. But at least for the spring and summer, all that new greenery busily consumes carbon as it photosynthesizes. It’s something the humblest plant does with no expectation of reward or recognition – but through OCO-2, their feat is revealed anyways.

The more green space these cities have, the more pronounced will be the spring/summer dip in carbon dioxide that OCO-2 measures. In spite of this, recent photos from airplanes show that an estimated 28.5 million trees are being lost in American cities every year.

Flint’s green space, on the other hand, has actually increased as the population has fallen in recent decades. This means, Maryum notes, that some Flint residents view city green space negatively now – perceived as a symptom of city decay. But at a community forum to talk specifically about the green wall, the 160 people who showed up were ecstatic. “They could see the purpose of it,” Maryum says. “They were really interested in the wall being interactive and having educational signs to learn from, and they had ideas about growing fruits and vegetables on it.”

Maryum herself feels “beyond excited” to eventually have the green wall installed. It will create one more piece of city infrastructure to serve as a carbon sink and ultimately arrest, in a small way, the rising concentrations of carbon dioxide. As this situation evolves happens in cities across America, OCO-2 will be there to keep tabs on those changes.

Acknowledgements: Ishita Pal, a Community Science Fellow with the Thriving Earth Exchange, and Kaylah Baker of the Sylvester Broome Empowerment Village, contributed valuable information to this article.